What do the diasporas from Turkey talk about (online)?

An exploratory attempt made by Daghan Irak during his visit.

Post

Immigration is a reality of today’s world, and also an economic staple for European economies. Since the immigrant communities from various countries had helped revive the European welfare, figuratively and literally cleaning up the remains of the Second World War; it rapidly became apparent that these communities were there to stay, for good. As the second and third generations emerged as citizens of the “hostland,” these communities evolved from a group of individuals to vibrant communities with complex actions and strategies. Today, we tend to call these communities as “diasporas.” Diaspora used to be a term exclusively employed for genocide survivors, such as the Jewish and the Armenian communities, however in our times, the scope of the term has enlarged, in line with the immigrants constituting important communities in the host countries. In one of the widely accepted definitions of diasporas, Safran (1991:83-84) qualifies diasporas according to six criteria; “they or their ancestors, have been dispersed from a specific original "center" to two or more "peripheral," or foreign, regions; they retain a collective memory, vision, or myth about their original homeland; [...] they believe that they are not—and perhaps cannot be—fully accepted by their host society and therefore feel partly alienated and insulated from it; they regard their ancestral homeland as their true, ideal home and as the place to which they or their descendants would (or should) eventually return—when conditions are appropriate; they believe that they should, collectively, be committed to the maintenance or restoration of their original homeland and to its safety and prosperity; and they continue to relate, personally or vicariously, to that homeland in one way or another, and their ethnocommunal consciousness and solidarity are importantly defined by the existence of such a relationship.”

In the case of communities originated from Turkey <a href="#_ftn1" name="_ftnref1">[1]</a> in Europe, we can easily observe that these conditions are overwhelmingly present, especially among the guest workers introduced from rural regions of Turkey to the big cities of Europe in the 1950s onwards and their descendants, which constitute a vast majority of people from Turkey abroad. Their relationship with the “homeland” can be summarized in one word that is unfortunately untranslatably to other languages; “gurbet.” Gurbet means “being abroad” but it also refers to a sentiment of longing towards the motherland and everything left behind. In the colloqiuial Turkish language, these people are never called German-Turkish or French-Turkish, they are simply “gurbetçi,” the ones who are in gurbet.

While <em>gurbet </em>mostly entails a very emotional state of mind on matters regarding the “homeland,” the political power that the diasporas from Turkey hold is a double-edged knife. As double-citizens, in most cases, they are able to vote in both countries. For example, in France, it is estimated that there are over 700,000+ people from Turkey (according to INSEE and TR Ministry of Foreign Affairs numbers), half of whom are also French citizens. In Germany, the figure is three millions, an electoral power that can easily tip the scale in critical situations. During the reign of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Islamist-populist who has recently embraced an anti-Europe and ultranationalist discourse, things have got complicated. Turkey has several official institutions in Europe, notably on religious matters, that are now working as part of Erdoğan’s well-oiled propaganda machine. Also, some political parties have recently emerged in the European countries, like PEJ in France, that seem to be forefronts to further Erdoğan’s agenda of using the diasporas politically against their host countries.

As part of my postdoctoral research at MédiaLab Sciences Po, I decided to work on the Twitter interactions (mentions and retweets) of the diaspora members from Turkey in France, using the Social Network Analysis (SNA) method. My work intentionally followed the footprints of <em>e-Diasporas Atlas </em>(2012), the stellar work coordinated by Dana Diminescu, and realized by the collaboration of Médialab. The work of Diminescu and her colleagues also depended on the SNA, using diaspora websites from different countries (the Turkey section was conducted by Sylvie Gangloff) to create a network map of diaspora communities. The most important part of that work was that it used digital data to show diasporas are complex and multi-layered networks with affinities and differences in between. My work also took this principle as a reference, however, what I wanted to advance that study to make a contribution to the field was to work with individual Twitter users. This preference, inevitably, brought along some methodological difficulties.

As an exploratory attempt, I designed my research around a sampling method that used Twitter’s search engine (not the API) to detect Turkish-speaking users in France, using Jefferson Henrique’s tool <em>GetOldTweets</em>. This choice had two caveats; firstly, detecting location of a user on Twitter is arduous task (Graham et. al, 2014: 569-570). Secondly, in order to cover all the major cities that the diasporas from Turkey live, I had to keep my data collection coordinates wide as possible, which caused some data being collected from neighbouring countries with Turkish-speaking communities, such as Germany, Switzerland and Belgium. As a result, it became apparent that, while my method to detect the Turkish-speaking Twitter users was helpful, it was by no means acceptably accurate and it required a heavy and manual cleanup and verification process to have a usable sample, which resulted in only around a thousand users to be included in the sample, out of 40,000 detected by the method.

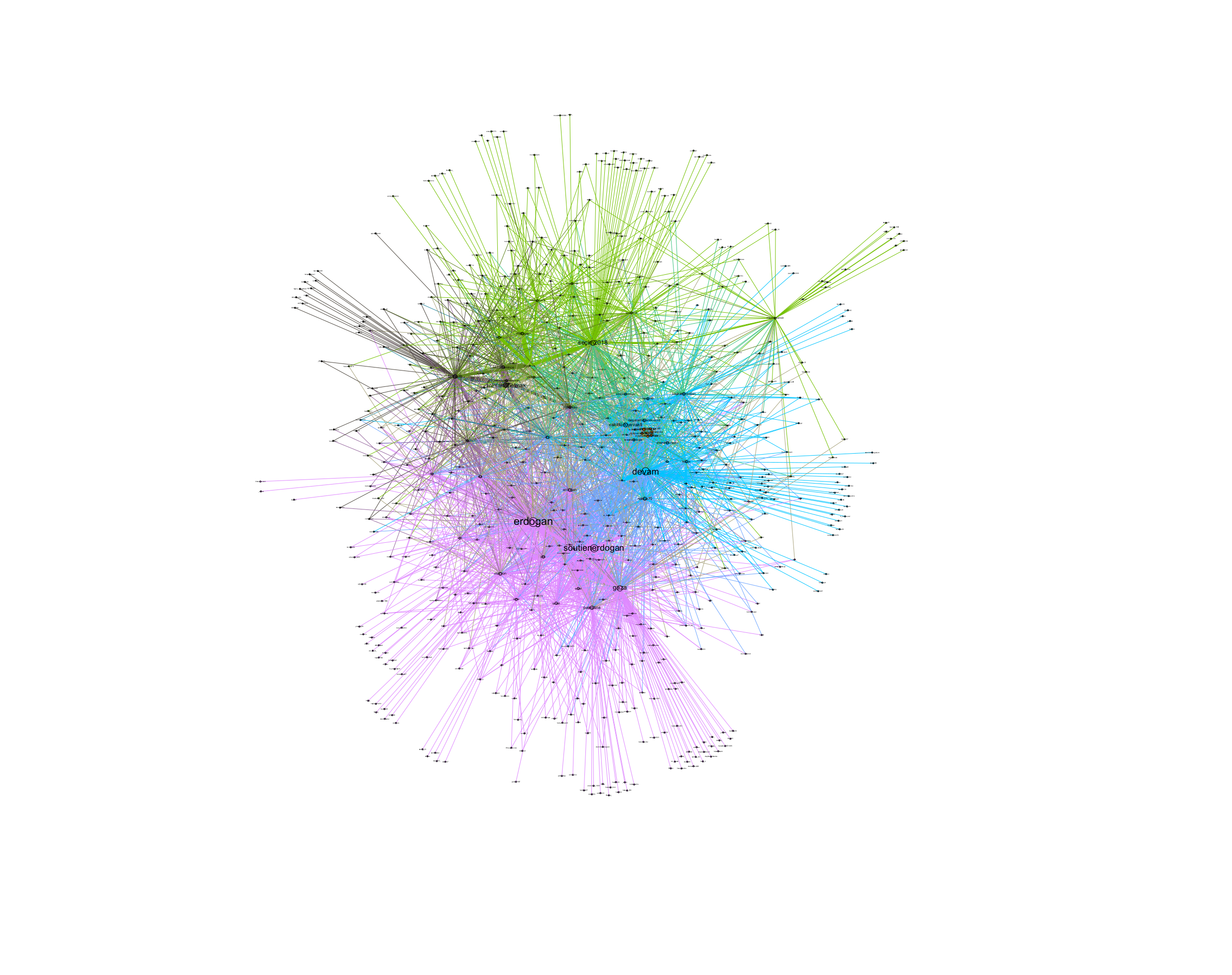

During my research, another problem that I could not have foreseen came to surface, presenting me an important lesson on diaspora sociology. The main criteria of my sample were living in France and posting in Turkish language. What I did not take into account was, even after teaching in France to undergraduate students from different origins, the third generation was more comfortable in using French as the primary language, and when they wrote in Turkish, they used a heavily <em>creolized </em>version of the language that only the French and Turkish speakers like themselves would understand. My method did not have the capability of detecting such usage in most cases, and a multi-variable search tool (that can detect users using multiple languages) should be created to facilitate that process. Whilst the creation of such a tool instantly topped my to-do list, I advanced my research using a more conventional method, snowball sampling. After snowballing popular diaspora users and the wildly popular French accounts of Stambulite football clubs, I had my sample of 1,500 total users ready. I collected the tweets of these users using the DMI-TCAT tool (Borra and Rieder, 2014) during the legislative and presidential election campaign between 17 April – 24 June 2018, to have over two million interactions. After cleaning up data, the SNA yielded the following results (Graph 1)

This network can be fully explored here : http://Daghanirak.com/diaspora2/

The most prominent result is; the political debate holds a rather minor place in the network (yellow, red, violet and blue clusters). While the yellow cluster mostly had the Erdoğan supporters, the red cluster included the opposition. The blue cluster is a mixture of political actors from France and Turkey; which suggests either the interest of the sampled users in the French politics or the French interest in the Turkish elections (or both). The violet cluster is mostly comprised of Kurdish users, which are isolated from other political interactions about Turkey. Bearing in mind, the pro-Kurdish party HDP was isolated from the opposition coalition in these elections, it is hardly surprising that there is still a stigma against the Kurds; however according to our observations the distance between the Turkish opposition and the Kurds are not as dramatic in Turkey.<a href="#_ftn2" name="_ftnref2">[2]</a>

One of two major clusters in our network (in green) is comprised of users interacting about football. As aforementioned, French-speaking Twitter accounts of Stambulite football clubs Beşiktaş (@_besiktas_fr, 5,3k followers), Galatasaray (@GSSKFRANCE, 6k followers) and Fenerbahçe (@Fenerbahce__FR, 6,5k followers) are by far the most popular accounts of this nature, and the football debate includes hundreds of young, mostly male, diaspora members. However, this cluster does not only include accounts related to the football world in Turkey, the French accounts are also present. Football is a very effective but often overlooked tool regarding diaspora members’ connections to the homeland and the hostland<a href="#_ftn3" name="_ftnref3">[3]</a>, and our research confirms that.

The final (pink) cluster should be one of the most surprising results of my research. This cluster is constituted by young diaspora members talking about daily things. There is no celebrity or politician influencer in this cluster. The most influencing users (according to the Eigenvector centrality calculations) are diaspora members, who are not at all among the Twitter celebrities called “<em>fenomenler</em>” (“phenomena”) in Turkey. This cluster has its own agenda, its own language, its own power relations; separated from the Twittosphere in France and Turkey. The diaspora members of North African origin are more likely to appear in this cluster than the Twitter users from Turkey. They are not into the politics of Turkey (they are likely to figure among the 53% of registered voters that did not vote in France), and they do not seem to be interested in French politics either. This cluster of young diaspora members, as well as the football cluster, needs an ethnography to be better understood; a work that could yield results changing our perceptions of the younger diaspora communities.

Finally, in an attempt to isolate political fractions in the network, I made another SNA graph, analysing users’ interactions with the political hashtags (Graph 2). According to this graph, the network is dominated by two major pro-Erdoğan clusters (cyan and blue), while two other clusters (grey and green) include pro-opposition hashtags and users. There is also a minor orange cluster that feature more engaged Erdoğan supporters. As we are used in Turkey and on Twitter in general, both sides attempt to “hijack” their opponents’ hashtags, but not to an extent that would render our graph hard to read. It should also be noted that the diaspora members engaged in political debates are probably older than the average user writing about politics in Turkey, so their lack of “digital nativeness” might have yielded a cleaner graph without tricks that required technological savvy.

The discussion of the Turkish politics on Twitter among the diaspora members in France are as polarized as it is in Turkey. However, in Turkey, because of the other democratic channels being heavily controlled by Erdoğan and his party, Twitter is a stronghold of the opposition where critical ideas are more likely to be expressed, even under conditions that Twitter is frequently throttled and the hundreds of social media users have been detained for “insulting the president” or “supporting terrorism.” In the diaspora map, the pro-Erdoğan camp is more dominant. This may be associated by the centre-left opposition being traditionally weak among the diaspora members in France, or the Kurds being unwilling to be openly engaged in political debates with the Turkish diaspora (the HDP is the second party in France, their participation in the discussion would change the map).

As a final word, it may be said that, while the diaspora communities’ engagement with the homeland and its politics continue, it is apparent that especially younger generations have their own agenda, different than their ancestors as well as their French coevals. A generational gap, especially on political matters, is likely to be present, which probably explains why Erdoğan cannot increase the overseas participation (50%, as opposed to 86,2% in Turkey) to the elections while he can comfortably win them (he received 52% of the votes in total, 60% in the overseas polls, 64% in France). Obviously, diaspora communities are complex social structures that require further research, my research is a mere exploratory attempt in these endeavours.

<a href="#_ftnref1" name="_ftn1">[1]</a> Throughout this article the qualifier “Turkish” will be exclusively used to define an ethnic category; not all the immigrants from Turkey, nor all the citizens of Turkey are ethnically Turkish.

<a href="#_ftnref2" name="_ftn2">[2]</a> For the difference between the diaspora and the homeland regarding the Kurds, see Van Bruinessen (1998, 2012) and Başer (2015).

<a href="#_ftnref3" name="_ftn3">[3]</a> I am currently co-editing a book and a special issue on this subject.